Marin Držić

The Calling of Father Marin Držić

2018

16 pencil drawings and an installation made from scrap of 292 pencils (Koh-i-Noor, 6B), previously used to create these drawings.

It is difficult for researchers, and almost impossible for some, to face the fact that they will never see a document that, according to their discretion and with regard to the material they already held in their hands, should have been preserved. So many disappointments happen; many hypotheses remain just assumptions without a firm foundation, like houses built on sand. Sometimes, however, even on the hillsides of the horizon we cannot find a single stone, so we build our sandy towers on the shores of the almighty ocean, which often relentlessly drags them into its depths. That is the world of researchers, the world of reason, logic and argumentation. Now imagine that only such a world exists, imagine that you have never seen anything that is not entirely subjected to argumentation or completely logical. What a sad and overly ugly world this would be. It would not know the vast depths of artistic creativity that does not exit the surface by the ways of reason, but rather by the paths of heart that lead into the unseen spheres of transcendence.

The marginalized part of the life of the greatest Croatian playwright and comedist Marin Držić (1508-1567), who has indebted the European, and thus the world history of literature, is undoubtedly his priesthood. So far no researcher has been fully committed to this aspect of Držić’s biography. One of the last articles on this subject was written by a historian Stjepan Krasić who at the very beginning of his article states that, in comparison with the works and expert analyses written about Držić, not a lot has been written “about another, not less important aspect of his personality: his clerical calling and activities and the reflection of his calling on his literary work”[1]. Insufficient evidence means too many assumptions, and after a certain number of centuries they cease to be satisfactory for a complete interpretation of a particular phenomenon.

One of the main assumptions related to Držić’s life, which has been repeated throughout history is the one about the tradition of the Držić family to send one of its members to the clergy. A common argument for this claim was related to the reasons for that tradition: the family managed the Church of All Saints, which was and remained known among the common people as the Domino church. According to the church patronage law, “from times immemorial” the Držić family had the right to suggest to the archbishop one of the two rectors, while the other was proposed by the members of the noble Gučetić family who were the co-owners of the church. Krasić notes that “missing the opportunity for someone from the family to come into that position meant a great economic loss for the whole family, that Držić family could not afford after they accumulated large debts in the XVI century”. Krasić, as well as many other researchers, thus suggests that Držić’s ordainment should be viewed within this framework, which allowed him at least some economic security. The first mention of Držić as a cleric was on the 12th of April 1526, when he was appointed one of the two rectors of the Church of All Saints. Until that point, that task was performed by Marin’s uncle Andrija, assumed to have given up his mandate and dotation in Marin’s favour. Marin was also given the task of managing another church at the same time, the Church of St. Peter on Koločep. It was customary that the head of the Domino church was also the head of the church on Koločep. It entailed the title of an abbot, even though it was not a Benedictine abbey. Držić thus became a double church prebendary. Next time the historical sources mentioned him was 12 years later, on the 28th of February 1538, when he became an organist at the Cathedral. That same year he enrolled into university in Italy. Unlike other clerics, Držić did not study theology. Instead he studied law at the University of Siena, for which he received the usual scholarship of the Dubrovnik government, which amounted to 30 ducats annually. In 1541 he became the Head of the Domus Sapientiae student hostel. The position itself was associated with the position of the Vice Rector of the University, which seems to have been really important. In fact, records show that Držić participated in the adoption of the new statutes at the University. Still, Držić never got a degree of the University of Siena although he was mentioned in Dubrovnik no sooner than seven years after moving to Siena. Shortly after his return, in 1549 to be precise, he was ordained a deacon and in 1550 a priest.

Perhaps the most logical argument to date aimed at proving Držić’s priesthood was “hereditary” was made by Krasić. The author believes that the absence of God and theology in Držić’s works is what inevitably proves Držić’s “lukewarm” attitude towards his calling. Držić does not negate God, but he does not affirm him either. However, the author himself explains that Držić was a child of his own time, a “product” of humanism that was striving towards reasonable and worldly criteria. About this kind of humanism Jacques Maritain wrote the following: “The misfortune of classical humanism was not to have been humanism but to have been anthropocentric”. Renaissance humanism does not deny either God or faith, but in comparison with the earlier period of the theocentric or the true Christian humanism, it significantly reduces the importance of transcendentality by turning more and more to the worldly. It believes that the man is his own centre and hence the centre of every reality. That is why the argument about the lack of God and theology in Držić does not seem strong enough to build any theories about his “forced priesthood” upon it.

When we try to give shape to something as intangible as the decisions of a man of the XVI century—because everything is a form, and life itself is a form, as Balzac said—then we turn to the artist. When science does not go in our favour it is a legitimate, and even a desirable act, to call upon art to open new gateways for us. The exhibition of Duje Medić, “The Calling of Dum Marin Držić”, will surely disrupt the already somewhat rigid attitude towards Držić as a priest who accepted his ordainment as a “family obligation”.

The painter-graphic artist Duje Medić (Makarska, 1986) is one of the most prominent Croatian painter-graphic artists and to put him alongside the great Croatian masters of the pencil—Adolf Waldinger (Osijek, 1843 – Osijek, 1904), Josip Vaništa (Karlovac, 1924) and Davor Vrankić (Osijek, 1965), with whom he exhibited in 2015, is neither exaggerated nor pretentious. We are talking about a layered narrator with a voluminous expression, a superb ruler of his extended hand—the pencil, a patient builder of black layers, an artist whose association are not unfamiliar, but they still surprise us and send us simultaneously to the past and the future.

The very unplanned, and apparently unrelated to the works we have in front of us birth of Duje’s Držić began in his artistic universe a few years ago when he became captivated with African masks at the Quai Branly Museum in Paris. He then drew in his notebook, on small papers of barely 10×14 cm, the most diverse masks built with grey tones on a white background. Their volumes were masterfully precise, so it is no wonder it seems that in this very moment we can separate them with our fingers from their background and put them over our faces. That is why ten Paris studies found their place in this exhibition. Without their direct visualization it would be almost impossible for the

viewer to justify the poetics of Medić’s Držić. Thoughts of Henri Focillon on how an artwork is immersed in the variability of time and the belonging to eternity, and how it is specific, local, individual and universal, interpret quite well the seemingly fragile link between African masks and Držić. Precisely those archetypal masks gave form to Duje’s reflections about Držić as a priest.

Although a work of art surpasses all its various meanings, and although around its interpretation, as Focillon says, “flourishes vegetation its interpreters decorate it with”, it still inherently allows all those meanings because they are all mixed within it. On this occasion, a sermon given by Bishop Mate Uzinić on the 3rd of May 2017, during the requiem mass for Marin Držić[2], offers itself as the key to the interpretation and understanding Duje’s perception of Držić’s priesthood, and thus his entire cycle about Držić.

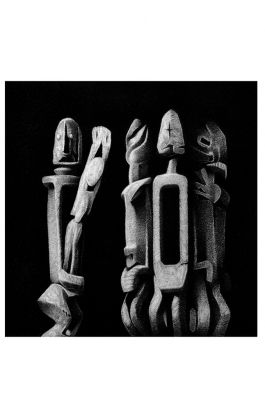

Duje’s “Would-be People 1” and “Would-be People 2” (25×25 cm) with their facial expressions are closest to the archetype of “the Parisian masks”. These are portrayals of faces which have and do not have human features in the same time. One moment they are irresistibly human, and the next they break apart and become mere elements of which something can and does not have to become human. Avarice and lust are what stops these elements to connect into a human being and thus become—as emphasized by Bishop Uzinić in the aforementioned sermon—“non-humans, without emotions, without the ability to pray and undergo a transformation that should have happened to them”.

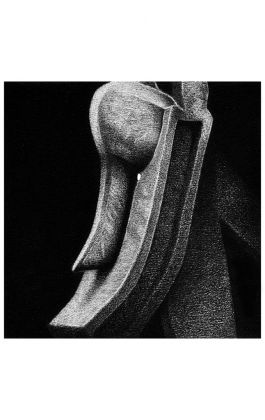

With his drawing “2nd of May 1567” (25×25 cm) Medić reminds us of the date of Držić’s death recorded by his nephew Jere. He drew curved forms, created according to the shape of human ribs. Medić gives them subtle symbolism by drawing three ribs which invoke one of many recounted conspiracy theories in the Republic of Dubrovnik, according to which the government sent three mercenaries to kill Držić after they learned he went to Venice to execute a “state coup”. The association with Držić’s death inspired the artist to put his pencil to work in drawing Držić’s portrait, a very ungrateful topic that many shy away from because there are no historical artefacts that could help us visualize in any way Vidra’s face. “Death Mask of Dum Marin Držić” (21×21 cm) thus becomes Duje’s contribution in the attempt to imagine Držić in his simple, fleshy humanity. The curious artist imagined a face with tired, almond-shaped eyes, an elongated nose and shapely lips. It is almost theatrical in its calmness, entirely like a mask made out of wax that can portray a kind of apathy, fatigue, and wandering thoughts.

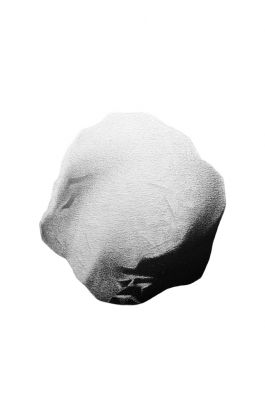

One of the most intriguing drawings in the exhibition, in the visual, but also in the interpretational sense, is Medić’s “1 Pe 2, 4-10” (25×25 cm). The artist approaches the first part of the First Epistle of Peter concerning the “new priesthood” in a very plastic manner through the simple symbolism of an irregular stone.

“As you come to him, a living stone rejected by men but in the sight of God chosen and precious, you yourselves like living stones are being built up as a spiritual house, to be a holy priesthood, to offer spiritual sacrifices acceptable to God through Jesus Christ. For it stands in Scripture: “Behold, I am laying in Zion a stone, a cornerstone chosen and precious, and whoever believes in him will not be put to shame.” So the honor is for you who believe, but for those who do not believe, “The stone that the builders rejected has become the cornerstone,” and “A stone of stumbling, and a rock of offense.” They stumble because they disobey the word, as they were destined to do. But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, a people for his own possession, that you may proclaim the excellencies of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light. Once you were not a people, but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy, but now you have received mercy.”

Medić here, more than anywhere else, draws closer to the thoughts of Bishop Uzinić about Držić’s calling being a real, divine call and not a call for the material. The Bishop pointed out that one of the greatest injustices posthumously inflicted onto Držić was the portrayal of his priesthood as something he was forced to do, although it is well known that there is no hereditary priesthood in the Catholic Church and that one cannot become a priest by succession. He considers that it is particularly unfair towards Držić to interpret his choice as something that was driven solely by material reasons that allowed him a potentially better position in the society.

In Medić’s stone one can easily recognize “the stone of stumbling” that during his life Držić represented by pointing in his works towards the non-humans in power and in society in general. However, undeniable is the fact that he himself became one of the “foundation stones” of the culture and identity of the city of Dubrovnik and undoubtedly its biggest bard, but also its brand, “the Croatian Shakespeare, Molière, Dante or Goethe”.

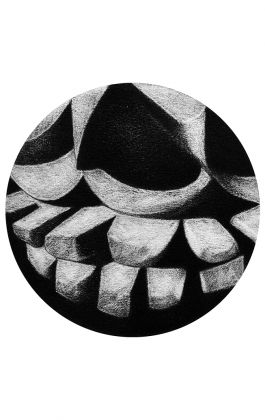

The theme of the stone leads us to the drawing “Building the Church (20×20 cm) Medić used to evoke the construction of the Church of All Saints (1457), where Držić was a rector and which is attached to today’s House of Marin Držić, a typical Dubrovnik town house where Držić probably stayed during his time of service. The display of semi-abstract stone boulders can also be associated with the restoration of the church after the earthquake, which is still in its original place. In an equal, in some places completely abstract manner, Duje portrays several motifs: “Priesthood”, “Prophethood” and “Grievances of the Common People”.

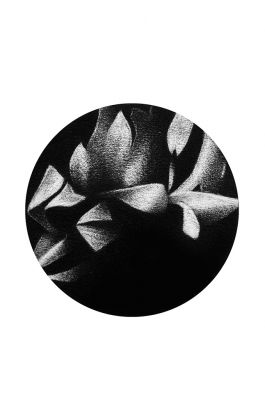

Medić brings a symbolic representation of the priesthood (20×20 cm) in a gentle, flourished and poetic form through which the priesthood is viewed as a sublime gift, a call from the Almighty Creator. This kind of reflection draws us back to the verses of the New Testament, more precisely to the First Paulian Epistle to the Corinthians (1 Cor 3: 5-10): “What then is Apollos? What is Paul? Servants through whom you believed, as the Lord assigned to each. I planted, Apollos watered, but God gave the growth. So neither he who plants nor he who waters is anything, but only God who gives the growth. He who plants and he who waters are one, and each will receive his wages according to his labour. For we are God’s fellow workers. You are God’s field, God’s building.”

One of the most beautiful and most unusual compositions of this cycle by Medić is undoubtedly the “Ordainment” (50×50 cm). The act of ordainment as receiving a lasting God’s seal on the soul and life of the one who receives it is depicted in the form of a floating, soft figure of Jesus Christ entering the womb of the chosen one to dwell within him for eternity. Three figures on the right side of the composition represent witnesses, with the archbishop ordaining the chosen one standing among them. His head is shaped like a mitre, and his body is symbolically indicated as a frame whose fulfilment can occur only in unity with the Lord. In the same manner, with square bodies and bent

legs Medić draws “Family” (50×50 cm) as a reflection of the physical and spiritual communion that is the foundation of society. In it Držić is represented by a central character with a sign of a cross on his forehead. He thus “earned” in the eyes of God a lasting blessing for his family whose centre is now in him, a God’s servant and the chosen one.

Medić continues to intuitively build his own story about Držić. “Prophethood” (20×20 cm), or the neglect of this particular Držić’s attribute (a conclusion made on the basis of his timeless observations about the human and his antipode non-human) Bishop Uzinić considers the second posthumously inflicted injustice onto Držić. It is very likely that precisely due to his gift of prophecy Držić had to leave his native Dubrovnik. The soft form of something that is a half-flower, half-fruit seemed to the artist as suitable to show the fragility of the gift of prophecy.

The broken form of the drawing “Grievances of Common People” is juxtaposed to the tenderness of a flower bud in the “Prophethood” drawing. It seems to be its bad, amorphous version. Duje directs us to the source of his reflections on the negative side of the common people as a whole through the words of his former professor, Ivo Šimat Banov, who once said that people are an amorphous mass that conforms to the ruling regimes and populist tastes. The artist in his works in the last couple of years uses amorphous forms to depict the negative and black flip side of the topic he is working on.

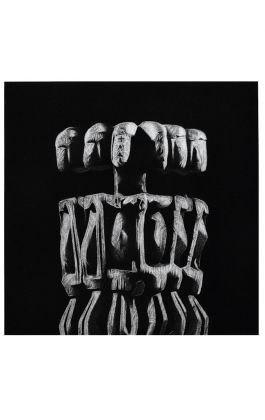

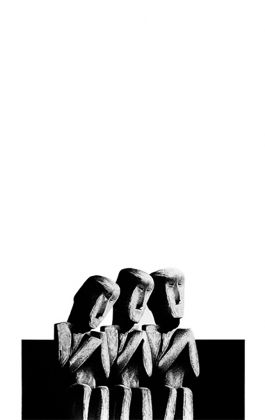

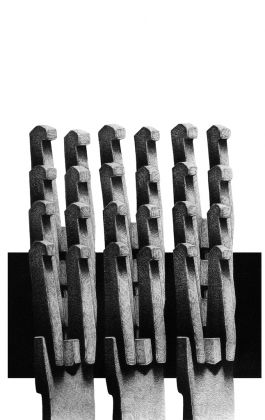

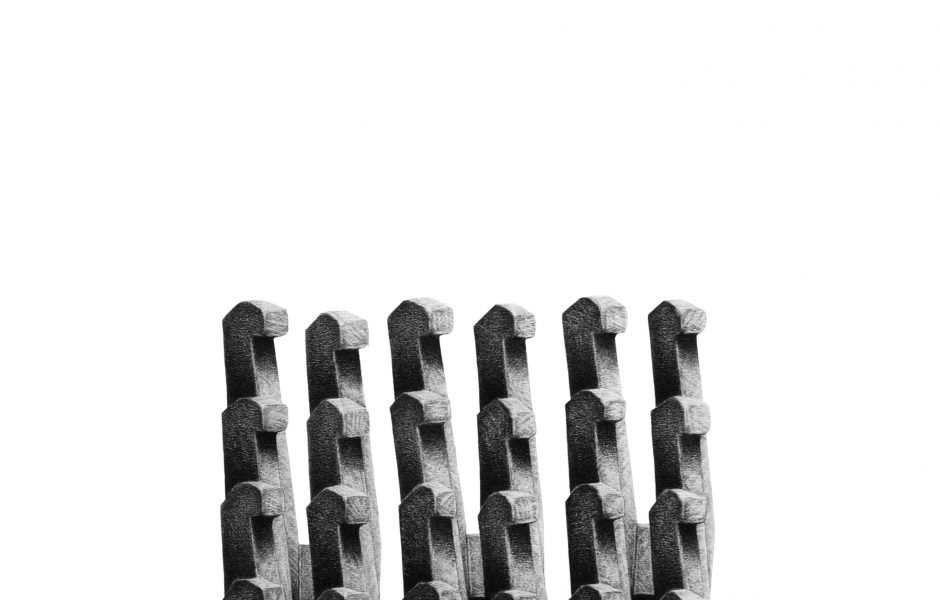

The drawings “Bench” (50×50 cm) and “Common People” (50×50 cm) further unfold the social component of Medić’s cycle. Bench thus represents a humorous representation of the common people in a complete generalization. These are “ordinary” people who sit in the church pew and pray the rosary or listen to the mass, people sitting on a park bench and chatting, people sitting on a similar bench in the tavern, drinking and playing a game of briškula, people sitting on a bench in Duje’s birthplace, playing boules and cursing God and all the saints from heaven. The artist reveals the autobiographical aspect of that scene, or the typical bench scenes from his native Brela. The same people were portrayed in a drawing that again focuses on the common folk, but this time as a homogeneous, unified mass composed of visually entirely identical elements. Do they applause at a theatre show, do they make noise in a public space by resisting the will of those in power or by praising them with applause and approval, are they raising their hands to the heavens, pleading when they are in distress or humbly thanking God for some undeserved gift, are they taking weapons into their hands and as an army do they rise to defend their family and their country? In any case, in the drawing of Duje Medić they have become replicas without human features, a dehumanized form that at a subconscious level still resemble people unified by the same goal. The “Preacher” (50×50 cm) separates himself from such a single entity; he is placed vertically on his black rectangular backdrop, from which we cannot separate him and with which he forms the shape of a cross. The preacher is caught at the moment of raising his voice which is shown by raising his hands, but there is no one around to hear his warning. Therefore, there is nothing left for him to do but to go somewhere else where someone can hear him.

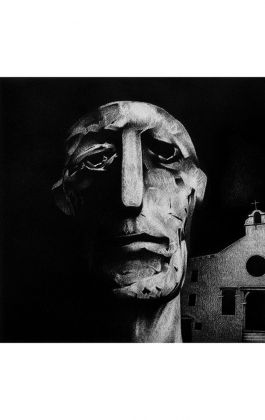

“Trip to Venice” (50×50 cm) is the last station in Držić’s life. The artist portrays it as a departure to the “hostile” Venetian territory where Držić could seek help in the fight against the corrupt Dubrovnik government, an act historians interpreted as an attempt to execute a state coup. To the left side of the throne two Dubrovnik patrons are shown to whom Držić “turned his back” in order to seek help from the Venetian Doge. Držić in the middle of the semicircular, dynamic composition, depicted with raised arms in which it carries something like a chapel or the tablets of stone Moses brought from Mount Sinai. The exaggerated grimace on which Držić stands undeniably evokes the laughter of a court jester, scoffing at the whole situation. This completely surrealist composition of hovering structures brings back into recollection the form of the Dubrovnik galleys. Duje’s trip into Držić’s world in this cycle ends with a drawing showing another portrait of Držić carried out in a somewhat fragmented form. By emphasizing Držić’s nose, the artist remains close to the earlier perception of Držić, most prominent on Ivan Meštrović’s sculpture of Držić. In the background of the portrait, the Domino church and the House of Marin Držić are realistically depicted. In his last drawing from the cycle, the artist relied on Donatello’s “Zuccone” sculpture, believed to represent the Prophet Habakkuk, in order to give Držić the qualities of a portrait. The atmosphere of the picture itself is somewhat disturbing. Držić’s face comes out from the dark background into the foreground of the drawing. It is impossible to avoid his distant gaze, his serious, hard mimic petrified in front of us.

Only an artist of great erudition, curiosity and patience could build with his shadowy and solid forms a world of the future that is nothing but the world of the past, and his universal ideas completely translate it into the present. It is a supernatural world, distant and full of secrets, but it is also quite realistic in its associations and symbolism. Apart from his “completely accidental” surrealist forms in which the figures sometimes come close to the characters of non-European cultures, and the ideas are represented with the help of the abstraction method, nothing seems distant and unfamiliar. Držić’s world completely occupied the artist, who incorporated in his drawings possible biographical information, as well as well-known literary lessons. Duje’s Držić is at the same time very close to us, but it is also brand new. In the process of creation the artist chose sides, as opposed to the researcher from the beginning of this narrative, and meticulously defended his own thesis based on his specific artistic speech, in all its layers, shadows and solid, stoic volumes. Medić does not use a pencil to sketch or draw contours. Exactly the opposite, he gives the strength of stone or wood relief to the seemingly fragile trace of pencil on paper. Only in his smaller pieces he alludes to the web-like softness of his tool.

With this exhibition, the House of Marin Držić puts in front of the viewer drawings of a great master of pencil who uses his astonishing forms to bring out an unjustly forgotten theme considered as somewhat banal. “The Calling of Father Marin Držić” of Duje Medić, besides focusing on the priesthood of this great Croatian and world playwright and comedist, serves as a call to all of us to open our eyes to something different, to think, to seek and to look back where history has not yet said its last word. The contribution of Duje Medić can only be an incentive for researchers of Marin Držić to give even more of their hearts, and to give their all for exposing the truth about the priesthood of Father Marin Držić.

1 Stjepan Krasić, “Marin Držić, the Restless Cleric”, Dubrovnik (Matica Hrvatska), 19, 2008, pp. 5–14.

2 Bishop of Dubrovnik Mate Uzinić, “Mass for Don Marin Držić, Dubrovnik Priest and True Propher”, website of the Dubrovnik diocese, published on the 4th of May 2017