Badlands

Badlands

2013

13 pencil drawings and an installation made from scrap of 618 pencils (TOZ, 6B), previously used to create these drawings.

In The Prince, Machiavelli wrote that “because fortune is a woman, […] it is necessary to beat and coerce her“ 1, or as repeated elliptically by Držić: “Fortune is not as woman shown for nothing.” 2 Numerous stories have focused on binding women to “fortune”, that is to faith – a woman’s charm would trigger a man’s passion (a biological fact), leading to the demise of individuals (Samson), nations (the Trojans and the Greeks), or the entire humanity (through the forefather Adam). Women have been perceived as holding the destiny (as fatal), in a mystical and dark manner, and the desire for them may eclipse one’s mind, causing violence and destruction to the one who desires and all that surrounds him. The title for this exhibition of pencil drawings by graphic artist Duje Medić has been taken from the song Badlands by Bruce Springsteen, about a subject disappointed in love.

At the basis of the fatal woman character are eros (as the drive behind human action), fear and anxiety over physical fulfillments of sexual desire being denied, as well as the woman’s coldness and unavailability. This attitude is fully assumed by Klimt’s Judith (1901) and Hygea (1900-07), but also in his portraits of Viennese women, depicted at the historical moment of liberation from being subjected to men. Therein lies the male fear: the loss of control, the insecurity of equilibration in human relations, the negation of character strength and assertiveness (traditionally considered by men as exclusively male characteristics) when colliding with an equal partner. The inspiration behind Courbet’s painting The Origin of the World (1866) holds vast importance for this series and the depiction of the said fear: a sizable, wide spread vagina is shown as the dark unknown, the heart of darkness, but also as the object of inconceivable lust eliciting fear and respect one would have for the Creator. In a novel by Ivo Andrić, Death in Sinan’s Monastery, the righteous and wise pilgrim experiences dread during his death, having remembered a frightened woman he had seen a long time ago and the forbidden lust he had felt at the moment. He turns to God and concludes that “the world begins and ends with a woman”, human passion and desire are inevitable, and it is therefore “more difficult than had I expected, to serve under the laws of your land.” And the laws are those of lust and passion. There is no willpower strong enough to negate the dark human nature, not even in the case of the spiritual teacher known for his calmness and moderation.

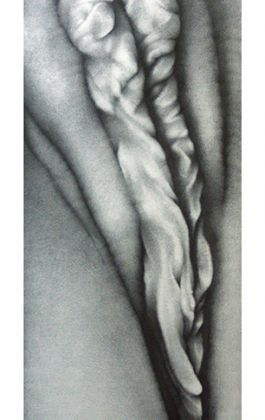

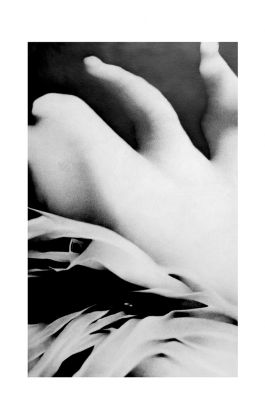

Duje Medić conveys this fascination in two large drawings – the drawing The World depicts a withered vulva with HPV scars, as a symbol of the lack of idea, illness and sterility of the present day society, while The Brave Old World uses the same format to depict a much more pleasing vulva, with lips smooth and soft in

texture, with playful lighting that leaves the impression of the feathery rippling of silk. The two vaginas are the two poles, where “the world begins and ends” for Andrić, misogyny and infatuation with women, a fear similar to Courbet’s, and fascination with inconceivable mystery. The drawings reveal proficiency in pencil manipulation, texture definition and lighting creation using solely grey toning. Impressed graphite, the meticulously applied black and light shading all form highly realistic scenes, ranging from sharply delineated details to sfumato. The heavy paper that the author chose for the basis insists on neutrality, leaving marks with the minimum of feedback. On this paper, the pencil acts like magical mist, or dust (seeing as drawing means fixating graphite dust), creating scenes, world and impressions with exceptionally high sensibility on the surface of a reality that is stiff, empty, undisputed, often boring and desolate. Artistic imagination serves as counterbalance to the bad land from the exhibition title (or to Eliot’s waste land), much like the power of art breathing sense, or at least an illusion of it, into reality. The present worldview is a pessimistic one, as apparent from the above clarified meaning of the drawing The World, but also from the somber tones present in other works, and the darkness from which the symbols of fallen illusions emerge.

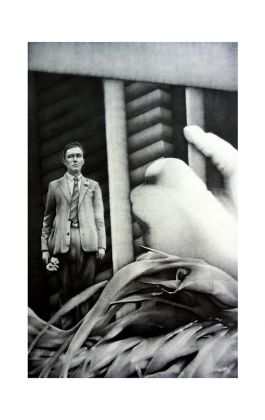

The drawing A Fool is therefore a manifesto, as it depicts a man with his eyes closed, holding a flower, as if waiting on his loved one. He is motionless, his facial expression calm and disappointed (in one word, stoic), revealing to us that the waiting is eternal and futile. The ideal woman from books and movies has in reality turned into a painful sensation of a scorpion sting, a permanent disappointment that still doesn’t stop him from waiting in a gentleman’s manner, holding a flower and no longer holding on to hope, but rather with his eyes closed, stubbornly denying reality, and defying all people and human relations, in which he no longer has any faith. A symbol repeated in each drawing is present here as well – a soaked crest and feathers from a slain rooster. It is a metaphor for castration, seeing as the rooster is the symbol of masculinity across all cultures, particularly apparent in those languages in which the same word is used to denote both the animal and the male genitals (e.g. in English, cock ). The present fear is that of castration as studied by psychoanalysis, yet even more so the artist’s disappointment in the present day world and society, in their sterility. In the above mentioned poem by Eliot, the rooster appears at the end of the last canto as a symbol of dawn and fertility, in order to emphasize the possibility for a renewal, the foundation of every myth.

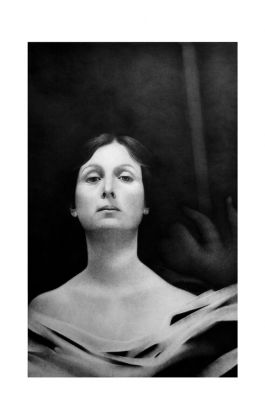

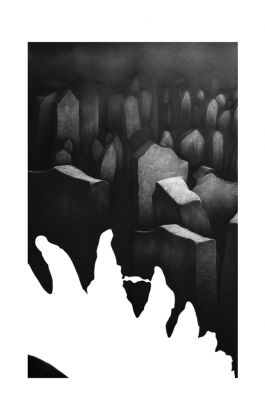

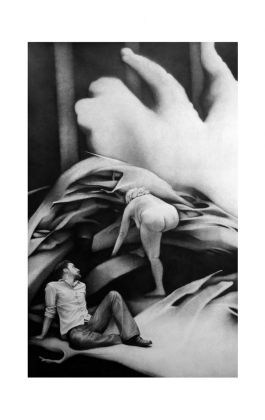

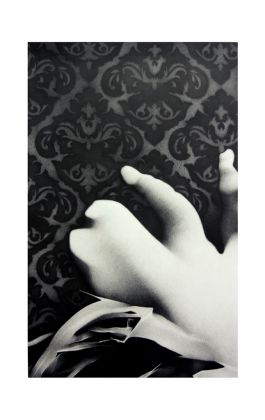

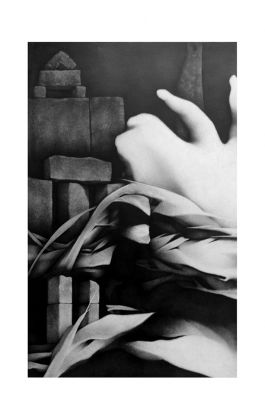

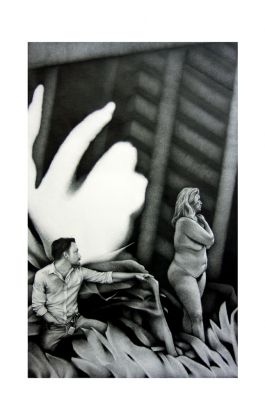

On the rest of his drawings, Medić (like Hesiod) exhibits an entire catalogue of women, a gallery reaching into various historical periods and cultures: Eve and Bathsheba from the Bible, Sarakaka from the Urubu tribe of the Amazon (known from the writings of explorer Francis Huxley), Belle Gunnes (who murdered her lovers, biological and adopted children for insurance fraud, accumulating a small mass grave in Indiana), Agnes Scuffs (who left her fiancé Edward Leedskalnin the night before their wedding, after which the crushed man built a huge limestone structure in Florida dedicated to her and known today as Coral Castle), Ilse Koch (the commandant of Buchenwald’s wife, who used to skin the murdered inmates), Mata Hari, Mathilde Schoenberg (the composer’s wife and Richard Gerstl’s lover), Patty Boyd (fatal to both George Harrison and Eric Clapton, who dedicated his song Wonderful tonight to her), and Isidora Duncan. Each drawing illustrates the story in a symbolic manner. Mathilde Schoenberg is depicted merely as ornament on the wallpapers used as the background in Gerstl’s portrait of her husband (1905); the ornament is used here as the symbol of the household atmosphere (seeing as the painter was a close family friend), conveying the bitterness of this love triangle. Isidora Duncan is depicted from a slightly lower viewing point, after a photograph taken between 1906 and 1912, resembling Klimt’s sensual Judith. Her emergence from the dark suggest the siren call of a woman irresistible to men, one that makes them fall to their own demise, like the Soviet poet who dedicated his last verses written in blood and alcohol to Isidora. What comes to the fore is the darkness present in the work of Medić, an impenetrable grid of strokes, the paper saturated in black to the point of object outlines piercing through. The skilled pencil manipulation is evident from the drawing Coral Castle, in which the varying intensity and character of the pencil mark achieve a highly authentic texture of massive limestone with rich shadowing on the rough surface. In several self-portraits, the author places himself in the position of David, the sinner king, or the subject from the previously mentioned song by Clapton, thereby underlining the deep sense of female pretense, to which this series of drawings offers a unique monument.

In the midst of numerous stories about ladies who destroyed lives and inspired artists, Duje Medić has made his selection and unraveled their essence before us. Much like his sizable vaginas (The Worlds ), the areas of fascination and rage, hope and disappointment, bitterness and beauty, that have marked women throughout the cultural history, are spread before the viewer.

Feđa Gavrilović

1 Niccolo Machiavelli, The Prince, The Penguin Classics, London: 1961 [Translated by George Bull.]

2 Marin Držić, Uncle Maroje, Summer Festival Dubrovnik, Dubrovnik: 1967 [Translated by Sonia Bićanić.]

Video invitation director: Luka Hrgović

Actors: Luka Hrgović, Nikolina Knežević-Pika i Duje Medić