The Sun

The Sun

2011

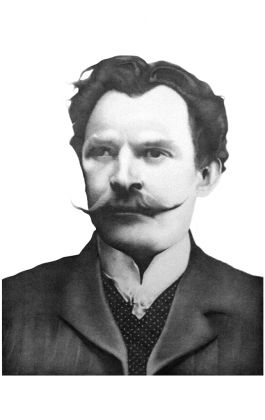

In the foot note for the poem The Lion of Chaeronea, published in his 1898 collection of poems, Silvije Strahimir Kranjčević clarifies the title of the poem (The name comes from a fourth century BC monument which was rediscovered and reassembled at the time) and says: “Oh, fortunate Hellas, with memories as these!” The poem depicts an image similar to the famous Fuseli drawing of a woman standing under the remains of a giant Roman monument dedicated to Constantine I, sometimes called Melancholy on the Ruins. The Lion of Chaeronea prompted the lyrical subject to contemplate the former glory of Hellas, its rich history and culture. In the exclamation which ends the footnote one can also sense the respect and awe the 19th century felt towards antiquity, as well as the desire to discover one’s own historical and ethnological heritage and its place in the world’s traditions. Apart from mourning for the past, the author displays a belief and trust in the present and future, but only if they base themselves on ancient values, symbolized by the monument from the title.

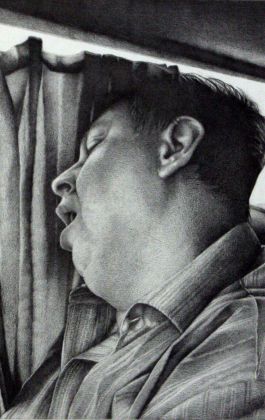

This approach to tradition is characteristic for the painter – graphic artist Duje Medić who, as part of this exhibition, presents a cycle of drawings in which he tackles the role of tradition in contemporary society. The exhibition contains portraits of the people who influenced the artist’s formation, the aforementioned poet Kranjčević, as well as the head of the folk dance troupe from Makarska, depicted in an unflattering pose, which can be read as a comentary on the reduced interest in tradition in contemporary times. The aforementioned portraits, as all the other works exhibited, are done in pencil and reveal a master at drawing: the lines are executed with extreme precision, and the shades of grey realistically depict the way light behaves making the drawings very credible. Tradition is ever present in this exhibition, as is the artist’s attitude towards creation: by turning to drawing his work emphasizes the importance of skill, art as craft – too often neglected in the art world today. A bunch of used pencils which lie strewn on the gallery floor testify to the physical work behind art and its physical result.

T. S. Eliot’s poem The Waste Land (published in 1922) depicts the contemporary world as a barren field where culture has lost its strength and declines in a long line of trivial and short-lived work. It is symbolized by a barren desert (The wasteland from the title) as well as the trash accumulated in the Thames (Even the title The Waste Land implies everything that is misguided and useless by using the word waste).

The artist shares Eliot’s attitude towards the state of contemporary society, which is evident in the drawing The World. The drawing depicts a dried up vulva, a barren womb. The state of today is shown to be in direct opposition to Courbet’s L’Origine du monde (a painting from 1866 depicting the same motif, not only as a source of erotic fascination but as a symbol of life itself). Opposite The World stands Revelation, a drawing of imposing Mouflon horns. Apart from their interesting appearance, horns generally symbolize cognition. This is why Moses, whose face was radiant with knowledge following his meeting with Yahweh, is usually depicted with horns on his head. In the poem Moses by Silvije Strahimir Kranjčević Moses is an idealist who believes in his people, and who is severely disillusioned once he finds them kneeling before the golden calf. The revelation in the case of this exhibition is the rising awareness of the wasteland which surrounds us; of the moral, esthetic and spiritual bankruptcy of the contemporary, where the museums are filled with simpleminded pseudo-political works, where in the spirit of contemporary relativism all esthetic qualifications are looked on with suspicion, and society is made weary by trivial affairs and cheap sensations such as sport, fashion shows and the celebrity culture.

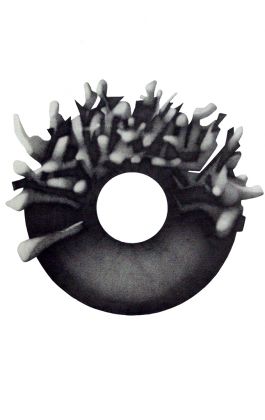

On the opposite side of the room stand the things the artist considers positive, symbolized by the large drawing The Sun. In a darkened circle, traditionally considered as the perfect form, appear irregular shapes suggesting sunshine. Next to this large circle the author has placed several smaller wreaths. Each of them contains varied forms which disturb their geometry. These variations are in fact deviations from the regular, interesting morphological inventions, which can also be interpreted as irregularities in the contemporary world, the waste which the human life has been reduced to, as in these lines from The Waste Land: The nymphs are departed/ And their friends, the loitering heirs of city directors, departed, have left no addresses. But what they have left is the “testimony of summer nights” in the form of various types of waste. The hopelessness which takes over the lyrical subject of this poem is analogous to Medić’s vision of the desecrated balance and tradition, evident in his entire oeuvre.

The artist pays homage to grass by depicting its dewy tips in drawing. Grass, which is today considered an inconsequential plant was once so important that the artist’s ancestors used to climb for hours in order to procure it for their animals. Although

it is very fragile, grass symbolizes progress so different from the one of the contemporary world, a vitalistic, biological growth, which with its importance in the food chain is associated with the interconnectedness of all living beings in the biosphere. The American poet Walt Whitman called his extensive collection of poems Leaves of Grass (published in 1855), and a line from his Song of Myself is applicable in this poem. “I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey work of the stars / And the pismire is equally perfect, and a grain of sand, and the egg of the wren.” The subject names a series of natural phenomena, finding in them a display of the power of nature, or how we would say today, the power of shaping the natural selection. The capolavoro of this exhibition is Man Looking into the Sun, a portrait of an old man made according to a photograph. The model rises from the darkness, the area he inhabits is but a small part of the large format of the drawing, but it is in perfect proportion with the rest of the drawing (the bigger empty space on the right side). In this way, the man dressed in traditional garments, the turban as an inheritance of Turkish rule and his monumental seated posture stands for tradition. The figure counterbalances the emptiness, ineptness and the alienation of our age. It’s impossible not to recall the long list of characters from Ivo Andrić, the oriental leaders in whom humanity and cold severity conflict. Sokolović from The Bridge on the Drina, Omer paša Latas from the Bosnian Chronicle. His gaze is directed towards the viewer as if posing the question: Will you – can you continue the tradition which is a part of all of us. “Here is the impossible union / Of spheres of evidence is actual / Here the past and future / are conquered and reconciled“ says Eliot about the meaning of creationin Four Quartets, his thoughts in tune with what Medić conveys in his art.

In the end, we can’t say Medić’s vision is entirely pessimistic. In the act of creation there is redemption and the design of individual existence. The message behind these drawings is sometimes dark and despondent, but it leaves behind the hope in the potential of revelation, in mythical characters (personalities of mythical proportions) such as Moses, Kranjčević, Elliot and many others in the long line leading to Duje Medić and his work. To the drawings executed with such mastery that their message is as powerful as the voice from the burning bush and subtle as a blade of grass.

Feđa Gavrilović