Parisian Studies

Parisian Studies

2016 – 2019

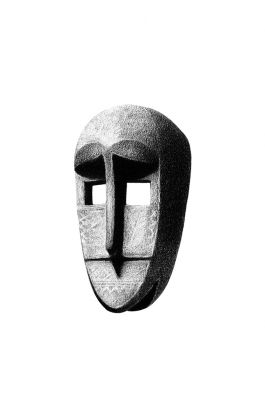

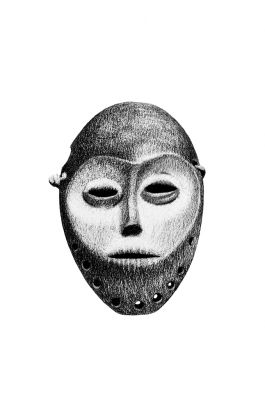

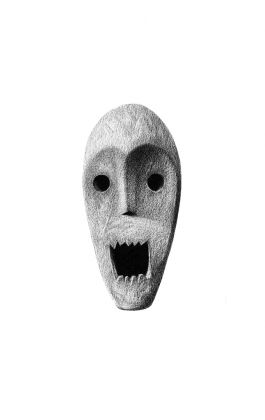

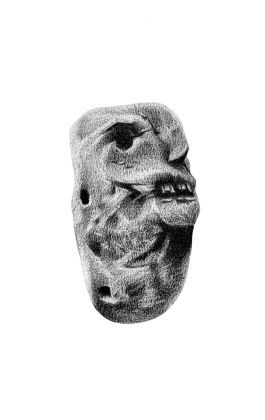

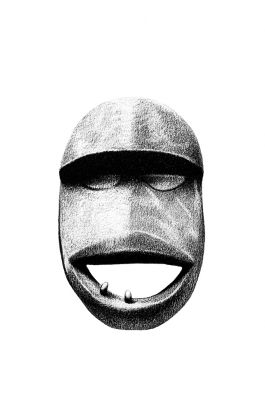

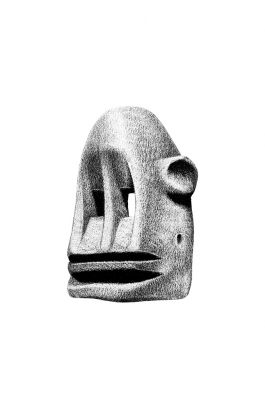

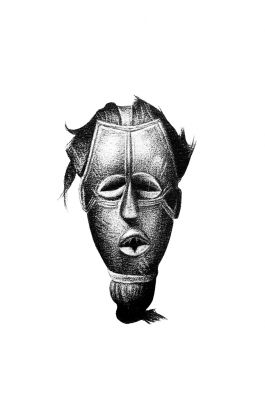

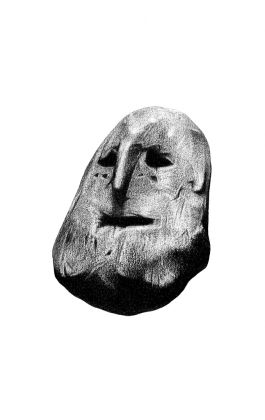

28 pencil drawings – art studies of museum pieces from Louvre and Quai Branly in Paris.

Parisian Studies of Duje Medić

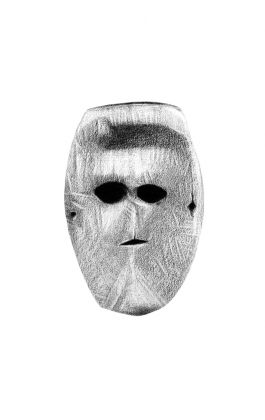

“Man is a creature in a mask”, says Oto Bihalji Merin in his great monograph Masks of the World published in 1970. It contains an overview of numerous masks used by man from the Stone Age to the present day as well as the functions of those masks in different rituals – the religious ones but also those that appear every day in the form of work equipment, make-up, clothing or behaviour. These are the objects to which human societies used to attribute magical properties, while attempting to establish communication with the world of demons and spirits, with the metaphysical foundation of human existence.

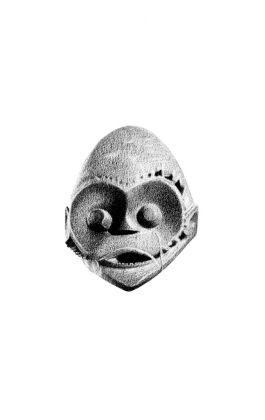

It seems quite natural that the masks of different (mainly African) tribes and the heads of their deities provided inspiration for the cycle of drawings by graphic artist and draughtsman Duje Medić, who is also an author fascinated by the mysticism of traditional culture. His encounter with the treasures of non-European art took part in the Quai Branly Museum, which was opened in Paris in 2006 and was founded following the initiative of the former President of the French Republic Jacques Chirac, in the tradition of his predecessors Georges Pompidou, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and François Mitterrand (each of these supported the construction of a single museum in Paris); all these museums were founded with the sole purpose of showcasing the artistic creation of different, mainly primitive cultures of the world. The expression and ability to reduce the form on numerous exhibits displayed in those museums compete and more often than not go beyond the freed imagination of modern and contemporary artists. This museum, which is a monument to both colonialism and humanistic universalism, enabled Medić to feel the power of traditional culture and another excuse for being fascinated by it. The faces embodying the forces responsible for the functioning of the physical world and the human soul spoke eloquently to him about man’s compliance with profound and unfathomable laws of nature as well as about man’s attempt to manage them. As Oto Bihalji Merin wrote in the above-mentioned book, a mask “allows its bearer to influence the supernatural forces that he is addressing but also to be transformed due to their effects. The bearer receives their substance and then transmits it to his or her co-tribesmen”.

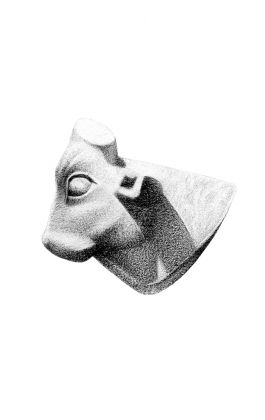

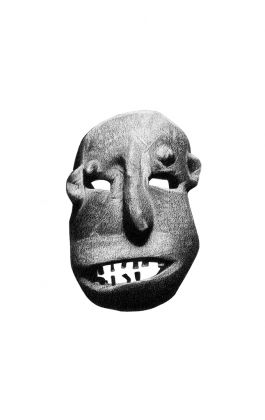

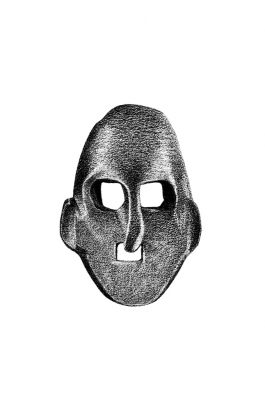

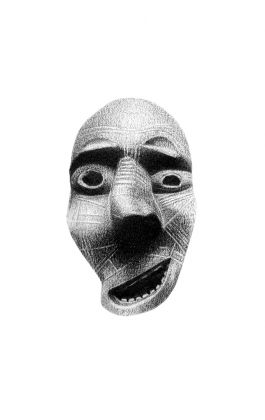

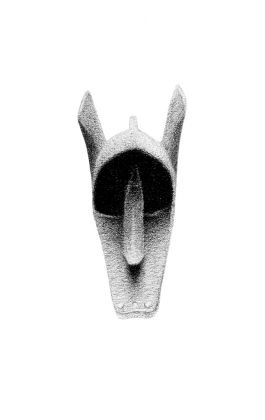

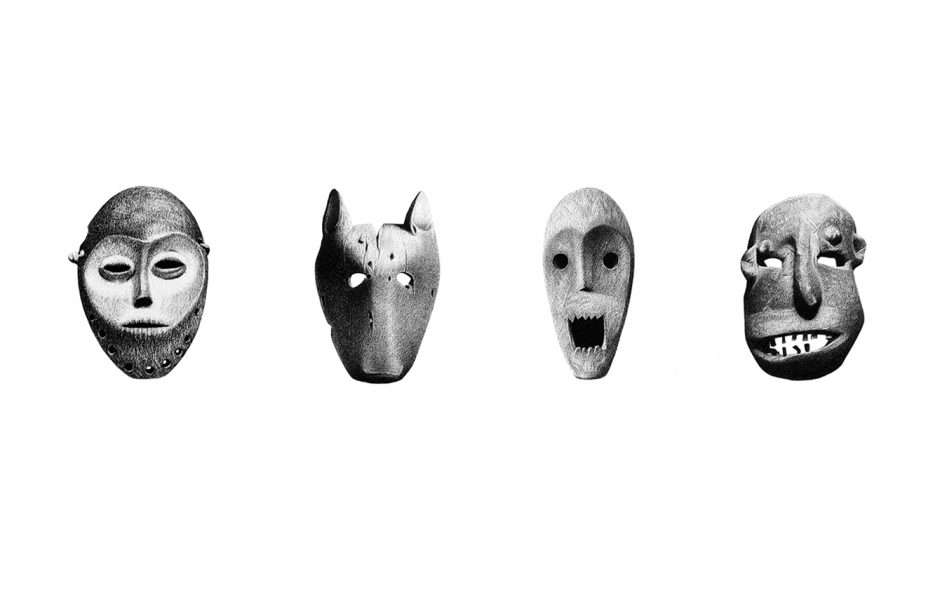

Traditional forms and motifs can be found in numerous Medić’s existing cycles but he has never wanted to exploit them in an aggressive manner or to make them adapt at any cost to suit today’s modes of artistic creativity, while consistently approaching them discreetly, with interpretative respect. Drawing ritual masks, mostly those from the Quai Branly Museum (along with several masks and figurines from the Louvre) was his way to honour the ancient sources of human consciousness of themselves, whose traces are still present in the artistic creation and religious ceremonies and practices of different cultures, including ours. With a series of small drawings of those holy objects, the artist conveys their compressed energy, elegant forms and radiating mystique to us. In his pen drawings these timeless forms look particularly monumental. While being reduced to grey tones between the blackness of the graphite and the blankness of the paper, they resemble human existence in this world between two nothingnesses. Skilful shading reveals numerous mesmerizing and dynamic faces representing deities and demons, which turn out to be nothing but human faces; they act as a disguise concealing our ancient fears and desires.

Feđa Gavrilović

Recollections of the Quai Branly and the Louvre

At the beginning of the 20th century, members of the group Die Brücke of Dresden started regularly visiting the Ethnographic Museum, where they revelled in the carvings of Africa and the southern seas. In the same way that Gauguin’s famed flight to Tahiti indicated contempt for the smugness of civilisation, the enjoyment of African art for these young Expressionists was a kind of escape from the ugly and oversaturated reality in which they had to live and work at the dawn of World War I. Numerous artists of the 20th century carried on with this partiality for extra-European art, and the discovery of the aesthetic quality of tribal art was particularly reflected in the figural sculpture of modern art. Duje Medić is one of the artists of the current time that have picked up from those whose art was profoundly immersed in the world of the totems, masks and figures of Africa, Oceania, Egypt and other ancient civilisations.

Creating since 2016 a cycle of ritual masks of African tribes, their deities and the idols of ancient civilisations, Medic has left his native ground, Brela, miles away. And yet Brela does constitute a point of departure for many of his drawings. Concurrently with these works, the artist did and exhibited drawings the subjects of which are connected with his native region, showing that being deeply rooted in the values of tradition is his internal motor, the generator that at the same time constitutes the connective tissue of all his pieces. Nothing can drive him again and again to test out his capacities as a draughtsman like subjects related to the tradition.

During his Parisian artistic residency in the Cité des Arts, visiting the Louvre and one of the most interesting Parisian museums, the Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, which is dedicated to non-European cultures, Medić found himself enthusiastic about the various depictions of these primitive civilisations. At that time he drew in his 10 x 14 cm notebook extremely diverse masks, built up in shades of black and grey on a white background. With masterly precision, he “carved” them down to the last detail, and it is not surprising if it seems to us that we can peel them off the background with our fingers and place them across the face, like some object that has a third dimension. He went on drawing this cycle after his departure from Paris. Revisiting photographs created during his residency, over almost three years, he developed his Parisian Studies, a series of thirty miniature drawings.

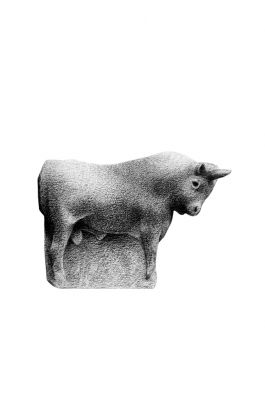

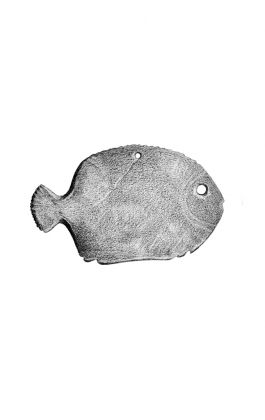

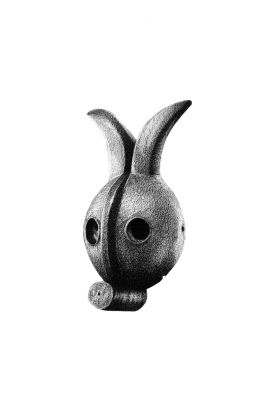

Duje’s masks are terrifying, witty, sometimes extremely poignant, and sometimes ironical. The visual rendering of these archetypal figures also influenced the expression of Duje’s drawings created after his Parisian discoveries. The atmosphere of the magical, the metaphysical and the absent, first of all in the masks, and then in all the other figures that Duje draws in this series (like the objects from the Egyptian collection – the monkey, calf, fish, bull…) is a special dimension of these works in which the artist builds upon technically perfect drawings. The figures in them are mute, caught and frozen in some timeless space, full of meanings that intrigue us, and yet are not burdensome to us. Sometimes they stand staring into the empty distance, sometimes looking right at us, or straight through us. Some are indifferent, some wondering, disgruntled, sneering, and some have a dignified seriousness. Developing them with a procedure of robust shading, he creates hyper-realistic depictions, achieving an impression of photographic precision, which yearns principally to imitate reality as perfectly as possible.

The thought of French art historian Henri Focillon that “the work of art is immersed in the variability of time and in affiliation to eternity and that it is special, local, individual and universal” is a very good interpretation of this “non-European” cycle of Medic, created in the heart of a Europe that has never been less European than it is today.

Anita Ruso